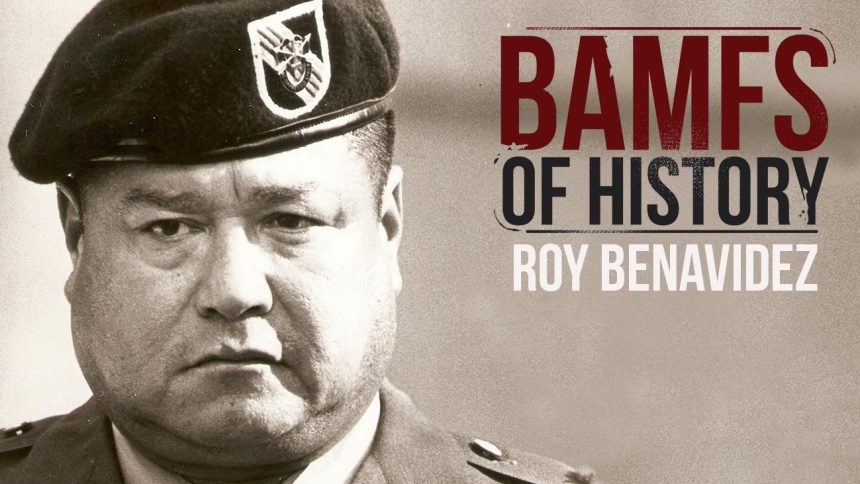

Roy Benavidez was a member of the United States Army Special Forces. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions during the “6 Hours in hell” firefight on May 2, 1968, in South Vietnam.

Early life

Raul Perez “Roy” Benavidez was born on August 5, 1935, in Lindenau near Cuero, Texas, in a family of a Mexican farmer, Salvador Benavidez, Jr., and a Yaqui mother, Teresa Perez. Early in his childhood, he lost his father, who died of tuberculosis. The same year, his mother remarried, and only five years later, she also died from tuberculosis.

After those tragic events, Roy Benavidez and his younger brother Roger moved to El Campo. There, they settled with their grandfather, uncle, and aunt, who raised them. Benavidez worked hard, from shining shoes at the local bus station to laboring on forms in California and Washington. He also worked at a tire shop in El Campo until he dropped out of school at age 15.

Military career

Roy Benavidez started his military career as a private in the Texas Army National Guard after enlisting in 1952 during the Korean War. Three years later, he switched from National Guard to Army active duty. In 1959, two significant events happened in his life. First, he married Hilaria Coy Benavidez and completed Airborne training. Shortly after, he was assigned to the legendary 82nd Airborne Division stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

After returning to Fort Bragg, he started working on admission to the elite Army Special Forces, known as Green Berets. Once qualified and accepted, he joined the 5th Special Forces Group and the Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG).

Vietnam

First tour and severe injury

During a routine patrol, staff sergeant Roy Benavidez stepped on a land mine and had to be evacuated back to the United States. He returned to his home state of Texas at Brooke Army Medical Center (BAMC) in San Antonio. Doctors told the young soldier that he would never walk again. The military began to prepare his discharge papers.

He refused to accept this diagnosis and began his own unsanctioned nightly physical therapy sessions in an attempt to walk again. Defying doctor’s orders, he would crawl out of bed at night. Using his elbows and chin to drag himself to a nearby wall, he would do his best to try to stand up. Eventually, he could prop himself up against the wall. His nightly sessions continued until he could wiggle his toes. After a while, he could begin to move his feet.

Following several months of excruciating pain (which he admitted would sometimes be so great it brought him to tears), Roy Benavidez could push himself up the wall using his ankles and legs. In July of 1966, after more than a year spent at BAMC, Benavidez walked out of the hospital, his wife at his side. Was he ready to take a medical retirement and go home?

No, he was determined to get back to combat in Vietnam. U.S. Army granted his wish, and, despite still being in great pain, he returned to combat operations in South Vietnam in January of 1968. When the average soldier serving in Vietnam was 22, Benavidez was already pushing 33.

6 hours in hell – a second trip to Vietnam

Roy Benavidez was awarded the Medal of Honour for his actions in the firefight called “6 Hours in hell.” In April of 1968, a 12-man special forces team was on patrol west of Loc Ninh, near the South Vietnamese-Cambodian border, when they ran into a 1,000-man North Vietnamese Army (NVA) infantry battalion. Roy Benavidez voluntarily boarded a helicopter to reinforce the unit and was dropped into the fight for his life.

He jumped from the hovering helicopter (30-50 feet/9-15 meters in the air) and ran 75 meters under heavy small arms fire to the team. I should mention that his only weapon was a KNIFE when he jumped from the helicopter. While running to his comrades, he was wounded on his right leg, face, and head. He took control of the soldiers, dragged half of the wounded to a Medevac helicopter, and then ran alongside the helicopter as it moved to pick up more wounded.

When he reached the team, Benavidez was severely wounded by small arms fire in the abdomen and had shrapnel wounds in his back.

As Benavidez returned to secure classified documents from the body of a dead soldier, the helicopter’s pilot was mortally wounded, and the aircraft crashed. Benavidez secured the documents, returned to the helicopter, and aided the wounded out of the overturned aircraft.

He gathered shocked survivors into a defensive perimeter. Under heavy fire, he moved around the squad and distributed water and ammunition to the men.

Then, he called for airstrikes and another rescue attempt. He was shot in the thigh a couple more times. While he was going toward the second rescue helicopter, he was stabbed by an enemy. He killed the enemy in hand-to-hand combat (despite his wounds).

When another helicopter came, he ferried the wounded, killed one of the enemy soldiers in hand-to-hand combat, and killed two others charging the helicopter from behind it.

After ensuring all the wounded were on board, Roy Benavidez collapsed but was pulled onto the helicopter in critical condition. Thinking he was dead, a doctor put him in a body bag and stopped zipping it up when Benavidez spat in his face. Benavidez sustained seven major gunshot wounds, had shrapnel in his head, scalp, shoulder, buttocks, feet, legs, arms slashed by a bayonet, and collapsed lung.

Medal of Honor

Sergeant Roy Benavidez was initially awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (the second-highest award for extraordinary heroism under fire) and the Purple Heart.

After more details of his heroism became known, Special Forces Lieutenant Colonel Ralph R. Drake initiated the paperwork for Roy Benavidez to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

However, the time limit to award the medal had expired. An appeal to Congress for an exemption to the rule in his case was granted, but the Army Decorations Board denied upgrading from the Distinguished Service Cross to the Medal of Honor.

The board requires an eyewitness account from someone present during the action. Benavidez believed there were no living witnesses. He didn’t know it at the time, but there was one man who lived and had witnessed his acts of heroism.

Brian O’Connor was a radioman on Benavidez’s team in Vietnam. He had been severely wounded during the fighting near Loc Ninh, and Benavidez believed him dead. He was evacuated back to the United States before he could be fully debriefed.

Fast forward to 1980, and Brian O’Connor lives in the Fiji Islands. In an Australian newspaper, he read a newspaper account of his former teammate’s brave actions.

O’Conner immediately contacted Roy Benavidez and submitted a detailed description of his eyewitness account to the Army Decorations Board. This was enough for them to upgrade Benavidez to the Medal of Honor.

In 1981, then-Us President Ronald Reagan upgraded the Roy Benavidez’s award to the Medal of Honour.

Aftermath

Roy P. Benavidez passed away at age 63 at Brooke Army Medical Center from complications of diabetes, but not before helping hundreds of service members transition to become civilians again. Roy was surprisingly soft-spoken and never took credit for being a hero. He’d always say:

“I am not a hero. The heroes are the ones who never came back. The heroes are the ones who are laying in their graves… the ones who gave up their tomorrows for our todays.”

Roy P. Benavidez, Medal of Honor recipient