Air Force Combat Controller (CCT) is a member of the United States Air Force Combat Control Teams, which are part of the United States Special Operations Forces. They are also referred to as special tactics operators. Combat Controllers (CCTs) are typically assigned to Special Tactics Squadrons, Special Tactics Teams, and other specialized units such as Pararescuemen, Special Operations Reconnaissance, and Tactical Air Control Party (TACP) operators.

Introduction

Combat Controllers (CCT) are a vital component of Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC), which is the Air Force’s contribution to United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), and Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC). Unlike their counterparts in the Army and Navy, Combat Controllers (CCT) do not typically engage in high-value target hunting and as a result, they are not as well-known to the general public.

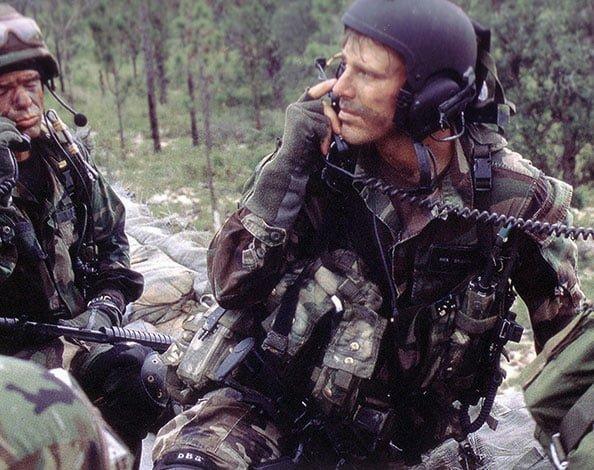

Their role is not to undertake high-profile missions, but rather to serve a specific purpose. Air Force Combat Controllers (CCT) are trained experts in all aspects of air-ground communication, including air traffic control, fire support (including fixed and rotary-wing close air support), and command, control, and communications in covert, forward, or austere environments.

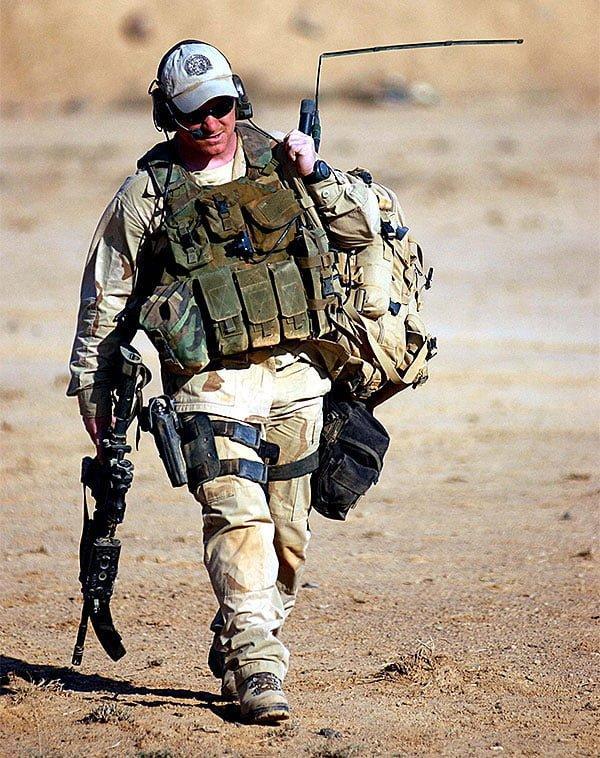

These Air Force special operators are often detached from other special forces units, which can contribute to the lack of recognition among the general public. They are often attached to other special operations forces within the US military.

Mission

Combat Controllers (CCT) are primarily tasked with deploying undetected into remote and potentially hostile environments and combat zones to establish landing zones or airfields for incoming troops. They also conduct air traffic control, fire support, command and control, direct action, counter-terrorism, foreign internal defense, humanitarian assistance, and special reconnaissance. It is worth noting that these individuals are FAA-certified air traffic controllers.

The motto of the United States Air Force Combat Control Teams goes by their mission, “First There,” reaffirms the combat controller’s commitment to undertaking the most dangerous missions behind enemy lines by leading the way for other forces to follow their lead.

History

The origins of the United States Air Force Combat Control Teams can be traced back to World War II. In 1943, Army pathfinders were created in response to the need for precise airdrops during airborne campaigns of World War II. General James M. Gavin, the Deputy Commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, established the Army Pathfinders to enhance the success of airborne operations by ensuring paratroopers were accurately dropped in their designated drop zones.

These pathfinders would precede the main assault forces into objective areas and provide weather information and visual guidance to inbound aircraft through the use of high-powered lights, flares, and smoke pots. The pathfinders were first used successfully in the Sicilian campaign. During the Normandy invasion, pathfinders jumped in before the main airborne assault force and guided 13,000 paratroopers to their designated drop zones. They were also used during Operation Market Garden to secure key bridges needed for advancing allied ground units. In the Battle of the Bulge, pathfinders enabled an aerial resupply of the 101st Airborne Division.

When the Air Force became a separate service in 1953, the United States Air Force pathfinders, later known as Combat Control Teams, were activated to provide navigational aids and air traffic control for the expanding Air Force. During the Vietnam War, combat controllers played a crucial role in ensuring mission safety and expediting air traffic flow during countless airlifts. They also served as forwarding air guides to support indigenous forces in Laos and Cambodia.

Training

Today, Combat Controller (CCT) training is a rigorous program that lasts almost 2 years. It is considered one of the most demanding trainings in the US Military. Upon completion of training, operators maintain their core skills as air traffic controllers and develop other specialized skills. They are highly trained in infiltration methods, including static line and freefall parachuting, scuba diving, rubber raiding craft, all-terrain vehicles, rappelling, and fast rope methods. Most of them also qualify and maintain proficiency as joint terminal attack controllers.

This rigorous training makes them one of the most highly skilled special operations forces in the world. It should be noted that only males are eligible for this training. The basic training is designed to develop initial strength and improve unique skills. It lasts 61 weeks and is divided into various phases:

- Special Warfare Prep (8 wks)

- Special Warfare Assessment & Selection (4 wks) – the screening course focuses on physical fitness classes in sports physiology, nutrition, basic exercises, CCT history, and fundamentals.

- Special Warfare Pre-Dive (4 weeks)

- Air Force Dive School (8 wks) – Trainees become combat divers, learning to use scuba and closed-circuit diving equipment to infiltrate denied areas covertly. The six-week course provides training to depths of 130 feet, stressing maximum underwater mobility under various operating conditions.

- Underwater Egress Course (1 day)

- Air Force Survival School (SERE) (3 weeks) teaches basic survival techniques for remote areas. Instruction includes principles, procedures, equipment, and techniques, which enable individuals to survive, regardless of climatic conditions or unfriendly environments, and return home.

- US Army Basic Airborne School (3 weeks) – Trainees learn the basic parachuting skills required to infiltrate an objective area by static line airdrop in a three-week course.

- US Army Military Freefall School (4 weeks) – this course instructs free-fall parachuting procedures. The five-week course provides wind tunnel training, and in-air instruction focusing on student stability, aerial maneuvers, air sense, parachute opening procedures, and parachute canopy control.

- US Air Force Air Traffic Control School (14.5 weeks) teaches aircraft recognition and performance, air navigation aids, weather, airport traffic control, flight assistance service, communication procedures, conventional approach control, radar procedures, and air traffic rules. This is the same course that all Air Force air traffic controllers attend and is the core skill of a combat controller’s job.

- US Air Force Combat Control School (12 weeks) – this course provides final combat controller qualifications. Training includes physical training, small unit tactics, land navigation, communications, assault zones, demolitions, fire support, and field operations, including parachuting.

This is considered the first part of their basic training, which earns them their initial certification and the right to wear the distinctive scarlet red beret. Following this, they undergo an additional 11-12 months of advanced skills training at the Special Tactics Training Squadron, Hurlburt Field, Fla., before they can be assigned to an operational special tactics squadron and deemed combat-ready as members of USAF Combat Controllers teams. It is a specialized program for newly assigned combat controller operators.

Combat Operations

USAF Combat Control Teams continue to be among the first to respond to international emergencies and humanitarian relief efforts. For example, during Operation Enduring Freedom, 85 percent of airstrikes were called in by Air Force Combat Controllers, according to then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld.

Operators from the Air Force Combat Control Teams have seen combat in every conflict the United States has fought since World War II. They have become an essential component in every operation on hostile territory, particularly since the emergence of the Global War on Terror. The USAF combat controller (CCT) operators have shouldered a significant workload. In the early days of the Afghanistan campaign, some Special Forces (SF) teams were deployed without a CCT, and the difference between those that had controllers and those that didn’t were dramatic.

It is safe to say that today, no one wants to go to war without them. They are highly respected, skilled, and in high demand, at a rate far greater than we could ever provide. Their efforts were critical in the early days of OEF and continue to be so.