“He died pulling the trigger. He died screaming into the face of the enemy.” The Canadian army has a policy on facial hair. Mustaches are OK, but beards are pretty much forbidden without medical cause, and even then, growing anything more extended than the allowed one inch is a sure way to bring a crusty sergeant major down on your head.

It is called a ‘jacking.’ And it’s what happens in the Canadian Forces when a superior officer has some issue with you or your beard.

Master Corporal Erin Doyle was not worried about getting jacked. He was, in fact, legendarily unworried about getting jacked. He may have been, to be honest, the least jacking-averse soldier in the entire Canadian Forces.

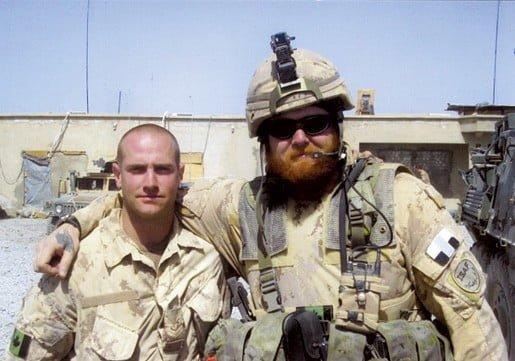

Seriously, he seemed to like getting jacked. It didn’t matter what the rank was doing the jacking, either, from sergeant to colonel; Doyle was as unworried about rank as he was about getting in trouble. I met Doyle, who was with the 3rd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, a couple of times in Panjwai in April 2008, and he made a singular—sort of scary—impression.

Doyle was a tattooed and wildly-bearded giant. He had the unmistakable swagger of a man for whom definite rules were mere suggestions. He had a way of leaning into a stare that could make anyone nervous. Hell, he didn’t just look at you; he estimated you. It was a look that seemed to leave everyone, even officers, feeling a little less than sure. It was an interesting effect, and I’m not sure where he learned it, maybe some finishing school for outlaws.

The first time I saw him, he was pretty literally presiding over a meeting between two sets of patrol leaders—one captain and one sergeant—during a long and arduous hike in the deep outback of western Panjwai.

The captain and sergeant would make plans, then quietly look up at Doyle. With a head shake and a grunt, he’d torpedo their idea, and they’d go back to the map. This went on for half an hour or more as gunfire and explosions rippled overhead. With his rank obscured by his gear—his battle rattle—I assumed he was a warrant officer or maybe the company sergeant major, based solely on the deference and respect he received from the other soldiers, many of whom I knew to be cynics of the first order.

When the planning conference broke up, I hurried to get up to where Doyle was, figuring I was better off standing near him than anywhere else. “This is bullshit,” Doyle growled at me as the two patrols finally moved off in the direction of the police substation at Zangabad, where he was then stationed. “Somebody thinks it’s a live-fire patrol exercise out here—on a two-way range.”

He had a point. There was patrolling with intent to achieve a tactical purpose, and then there was walking in circles in brain-shrinking heat to prolong the patrol to its preordained length. This was now clearly the latter. “What’s that patch mean?” I asked him as we walked, pointing at the symbol on his shoulder that featured the text ‘20%’.

Doyle explained that during a pre-deployment speech, the sergeant major complained that 100 percent of the problems in their unit were caused by 20 percent of the soldiers. He said it in a much more profane way than that, however.

Some guys, I thought, would hear that speech and silently tick off the troublemakers in his mind, some would smile inside knowing they may well belong to that club, some would embrace it by smiling openly and calling themselves a 20 percenter, and then some, probably a very few, maybe only one, would go out and get 20 percent patches made and have his whole platoon wear them into combat.

That last guy—that was Doyle.

But there was way more to him than just being a badass among badasses, as I learned the second time I met him a few days later. Not only was he the most impossibly polite outlaw you could imagine, being friendly to even outcast journalists, but the respect with which everyone treated him turned out to have a firm and undeniable basis.

On that day in late April, Doyle and his section had patrolled several hours down to Police Substation Haji—the place where he was eventually killed—to take over for another team that was being pulled out of the field.

![Doyle in Afghanistan in 2008. [PHOTO: COURTESY NICOLE DOYLE]](http://legionmagazine.com/en/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/erininset3.jpg)

Now, we’ve all moved heavy boxes before, and it’s not exactly fun. Doyle was already sick—with Afghan hantavirus, as he called it—but that didn’t stop him. He jumped up and moved boxes with his troops. And he pushed them way past the point where any average person would have stopped. He moved them until he nearly died.

No, really. I’m not just saying that. He moved boxes until he passed out, and his vital signs got so bad the medic came over the radio saying he was unsure if Doyle would live and requested an emergency nine-liner medevac back to Kandahar Airfield.

No one who knew Doyle is surprised by this story. Troops were in danger, so he pushed past all of the body’s typical warning signs because a job had to be done. It’s just what it was.

Doyle made it back to Kandahar, and with the help of a tasty intravenous buffet, he survived the day. He would not survive the war.

Numberless Are the Dead

Numbers are numbers, they tell you something, but it’s probably nothing vital. There is no code hidden in the numbers, nothing to say to you whether the war was just or if the man was loved or what life now feels like for the people he left behind.

Nonetheless, maybe significant digits do tell some story too, so here are some rough numbers. Doyle was the 90th Canadian soldier to die in Afghanistan since 2002. And he was approximately the 2,100th Canadian to die in the service of his country since the end of the Second World War, and very nearly the 118,000th soldier to have his name listed in the official Books of Remembrance since Canada first sent armed men overseas in 1884 to fight alongside the British in Sudan.

Beyond the numbers stands the other story. It’s Doyle’s story. And even more, it is the story of his wife Nicole, his friends and comrades, and the unimaginable cost of losing someone—one man—at war. These are the people whose world changed when Doyle died. And it’s not now a better world.

![Doyle with M.Cpl. Matt Yaschuk. [PHOTO: COURTESY NICOLE DOYLE]](http://legionmagazine.com/en/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/erininset4.jpg)

The news comes quickly.

The way they still speak about him in the present tense is one of the things you’ll notice if you talk to his friends.

Master Corporal Matt Yaschuk, one of Doyle’s best friends, is not the kind of guy who sits typically down for interviews with journalists; you can tell just by looking at him.

But yet, on a cold December day in Edmonton, he sat patiently, waiting for me, wearing a blue plaid jacket and a toque, his hugely muscled arms protectively cuddling a little Tim Hortons coffee.

Yaschuk was in the 3rd Bn. with Doyle, the same company, and had been for years. The two of them had been through a lot together. From Bosnia in 2000 to Kabul in 2004, they’d seen pretty much everything.

Yaschuk was at Forward Operating Base Sperwan Ghar, sleeping in on that early morning in August when Doyle’s section of about ten guys—at that time holding the Haji base all on their own—came under attack.

Commonly when a soldier is killed, the news is spread out to the unit all at once, as soon as possible. But in this case, because everybody knew Doyle and Yaschuk were so tight, he was told first. “A warrant officer came in and woke me up,” said Yaschuk. “He just asked me to come with him. And I knew there was a contact going on because I could hear the guns firing, but there’s always contact, rounds going out all the time, so you get used to that.”

The warrant officer took Yaschuk outside and told him Doyle was dead and that the fight was still going on. “He told me that Erin was killed. And then I felt like shit,” said Yaschuk sternly, with something that seemed more substantial than reluctance. “I just lost one of my best friends, and there’s not much you could do. He’s out there, and you’re in here. You wish that you were out there with him.”

Yaschuk was among the first of Doyle’s close friends and family to hear of his death. Many others still hadn’t heard, like Nicole, his wife of 11 years, or his daughter Zarine or his many friends or the rest of Canada, even.

It didn’t take long for Yaschuk’s higher-ups to tell him he would be going back to Kandahar with Doyle to follow his coffin up the ramp of the Hercules and escort his body back to Canada. “I was happy I was going with him. It’s the biggest honor I’ve ever had in my life,” said Yaschuk, looking down at his coffee. “But at the same time, I was pretty broken.”

Yaschuk and Doyle rode on the Hercules back to Camp Mirage, a nearby Canadian base, before transferring to a Canadian Airbus for the flight back to Trenton.

He remembers sitting those many long hours quietly, separated from Doyle by a draped curtain.

Waiting for Doyle and Yaschuk on the tarmac in Trenton alongside Nicole and Zarine were two other members of the tight 3rd Bn. crew, M.Cpl. Gerry Fraser and M.Cpl. Kevin Nanson had been on this tour with Doyle only to be seriously injured and evacuated to Canada.

Not incidentally, many who witnessed the scene believe Doyle probably saved Nanson’s life after the improvised explosive device strike. Nanson was so severely injured, but more on that later.

“It was emotional,” remembered Yaschuk. “Very emotional. Especially with Gerry being hurt.”

Fraser had been repatriated after suffering major injuries in a vehicle accident in Kandahar City.

![Kandahar, 2002. [PHOTO: COURTESY NICOLE DOYLE]](http://legionmagazine.com/en/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/erininset5.jpg)

See, Doyle used to love pranks. Whether it was duct-taping rotten yogurt to a guy’s locker or sending truly illicit emails from a friend’s accidentally left-open account, Doyle could always be counted on to cause trouble.

So, when Chief of Defence Staff General Walter Natynczyk approached the trio and said, quietly, conspiratorially, “Would it mean anything at all if I said to you ‘Hey ——!”

What Natynczyk said will forever remain a mystery to all but those who knew Doyle, but it may be enough to say that it was Erin’s favorite politically incorrect greeting.

The trio just shook their heads and laughed. It was as if Doyle had gotten them yet again, in the most unlikely way possible.

What had happened was that Natynczyk had asked Nicole if there was anything at all he could do for her, and she figured the boys could use a good laugh, so she put him up to it.

Nicole and Erin

Nicole Doyle doesn’t let many people call her Nick, and if you try for ‘Nicky’ you’d better have some armor-plating system to protect your softer organs from attack.

Nicole is in the forces too. She’s currently a corporal in the air force, she’s been to Afghanistan before, and she’s going back again.

Beyond that, she seems to share something way down inside with Erin: a love of mischief with a hard edge, impatience with weakness, and a strict policy of never abiding fools.

![Nicole and Erin in Bosnia. [PHOTO: COURTESY NICOLE DOYLE]](https://legionmagazine.com/en/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/erininset6.jpg)

She was right, of course.

The issue of when Nicole and Erin first met isn’t all that easy to resolve, but they were married on April 25, 1997. (I know this for sure because I asked this question twice.)

When Nicole was young, she moved out near the Westside area of Kamloops, B.C.

She remembers her school bus would stop on Dairy Road and pick up this redheaded kid who was always acting boisterous and wild. Later, Nicole remembers watching the same redheaded kid play football at Westsyde Secondary School.

The full article can be found HERE.

Biography

Born: March 20, 1976, in Maple Ridge, B.C. Grew up in Kamloops.

Enlisted: May 21, 1998.

Favourite activities: restoring old trucks and cars, shoveling neighbor’s sidewalks, playing pranks on friends and others.

Probable reason he was able to grow his beard so long: Doyle played Santa every year at the PPCLI Christmas party.

Gyms now named after him: two, one at 3 Battalion, PPCLI and another at 1 Bn., PPCLI. There was a third in Zangabad, but that base has been torn down.

He was scared of: heights, bees (he was allergic) and pretty much nothing else.

Surviving Family: Kathleen (mother), Melvin (father), Sean (brother), Barb Loucks (step-mother), Bob Mitchell (step-father) and Keari (half-sister).

His dreams for the future included: becoming a Search and Rescue technician, before retiring with Nicole to Valemount, B.C., where he wanted to pump gas.

Buried: St. Emile Cemetery, Legal, Alta., August 21, 2008.