Operation Flavius was a military operation conducted by the British Special Air Service (SAS) in Gibraltar against a Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) cell. The operation resulted in three IRA members who were shot dead by undercover operators of the British SAS on March 6, 1988.

The three terrorists – identified as Seán Savage, Daniel McCann, and Mairéad Farrell (members of Provisional IRA Belfast Brigade) – were believed to be mounting a car bomb attack on British military personnel in Gibraltar. Plain-clothed SAS operators approached them at a gas station, then opened fire, killing them.

Operation Flavius was subject to the special inquiry conducted by the British Government in the aftermath of the operation.

Introduction

In late 1986, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) had turned its attention to driving out the security forces based in Northern Ireland. In response, the British Government stepped up action to monitor the movements of IRA members in an effort to head off further incidents. As part of this escalation, the SAS began regular rotations of its soldiers into Northern Ireland to work with the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and the UK MI5 intelligence organization elements.

The IRA, however, had been at war with the British Government for over sixty years and had adapted well to the presence of the growing antiterrorist apparatus. By early 1987, the Republican guerrillas had perpetrated no fewer than 22 separate attacks on police stations alone. And while some incidents had been prevented, at the time, there seemed no end in sight to the ongoing urban war. However, a series of related events that occurred during this time would soon bring about a dramatic reduction in the IRA campaign.

Failed Loughgall Operation

In 1986, an IRA team had used a similar heavy vehicle in an earlier attack using a large explosive device placed in the JCB’s steel bucket. The vehicle was then driven through the closed main gates of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) station at The Birches, County Armagh, and the device detonated, causing significant damage. For this reason, authorities were on the alert specifically for thefts of similar heavy equipment. When just such a vehicle was reported stolen, in April 1987, RUC Security initiated an immediate investigation.

Following the theft of a JCB mechanical digger/tractor from a construction site in East Tyrone, an alert went up throughout the intelligence networks of the security forces. The digger was soon discovered, parked near a disused farm just 16 km from the RUC station at Loughgall. Suspecting an attack was soon to follow, security forces contacted the SAS. In short order, surveillance teams from the RUC’s E4A unit monitored IRA terrorists transporting explosives to a disused barn.

On May 8, the RUC intercepted a phone call between two group members: the IRA was ready to strike.

Immediately, a joint RUC/SAS team moved in around the Loughgall station, which had been quickly but quietly evacuated. RUC snipers took up position while SAS troopers spread out through the compound and nearby countryside (to prevent the escape of any IRA members following the attack). The intercepted call had also provided the SAS sample time to establish a box-type ambush centered on the most likely approach route.

At approximately 7:20 p.m., an eight-man IRA unit (actually two active service units – ASU’s – operating in tandem) approached the RUC station in a stolen blue Toyota van, followed closely by the JCB, laden with beer kegs filled with 500 pounds of explosives in its bucket. Following their plan, five gunmen exited the van. They opened fire on the compound, effectively preventing security forces from intercepting the JCB as it smashed through the main gate and made its way into the courtyard. The three terrorists (the driver and two armed guards) jumped from the tractor and ran towards the safety of the getaway van.

HOWEVER, the RUC and SAS had anticipated this, and as the terrorist entered the pre-established kill zone, they opened fire. Seconds later, the bomb was detonated. In the massive explosion that followed, a large section of the closest RUC building was demolished, as was another structure some 50 feet away. Chunks of plaster, steel, and wood were sprayed in all directions. However, the JCB’s bucket design directed the majority of the blast toward the RUC station. In the maelstrom that followed, all eight terrorists were killed.

Two civilians in a white Citroen car appeared in a tragic development, unknowingly driving directly into the ambush zone. Thinking that the car belonged to an unexpected IRA team, the SAS opened fire, killing the driver and seriously wounding the passenger. A later investigation revealed that these individuals had no affiliation with the IRA.

According to the standard procedure in counterterrorism operations designed to retain anonymity, British Army helicopters soon arrived to extract the SAS team and deliver them to a secure area.

For some time following the failed Loughgall operation, the IRA reportedly suffered from a significant disturbance within the group. Elements of the IRA leadership suspected that a mole had revealed the details of the operation to the security forces. This theory caused no small degree of disruption as the group’s internal security was reviewed and revised. In time, however, the IRA search for a mole proved fruitless, and it gradually accepted that the security forces were wholly responsible for uncovering the plan.

Having lost eight of its top operatives, senior leaders decided not to let Loughgall go unrevenged. And this time, secrecy would be paramount.

Operation Flavius

Following the dual setbacks of Loughgall and the elections, the IRA needed a victory against the British Government to demonstrate its continued viability and restore the confidence of its supporters at home and abroad. Target selection, therefore, was of the utmost importance. Operation Flavius was about to begin.

IRA’s most important operation

Having learned from Loughgall, the IRA began to plan for one of its most important operations. Following a brief period of deliberation, it was decided that the British presence on Gibraltar was the best of all possible targets for a number of reasons.

Gibraltar was considered a ‘soft target; British soldiers were commonly rotated to the peaceful location following demanding duty in Belfast as an unofficial reward. Security was, while not lax, much lighter than any that might be found in the calmest areas of Northern Ireland. So, while they were still on active duty and not on leave, soldiers could usually look forward to a long period of relaxation.

Why Gibraltar?

From an IRA perspective, this mindset was ideal. Additionally, and of equal importance, Gibraltar was one of few remaining locations in the world that still represented Great Britain’s colonial-imperialist power (much like that the IRA felt had been thrust upon it in Ireland). For this reason, an attack on the military presence there would inflict direct harm on British soldiers and stab at the heart of the Government in London.

Long-time IRA members Daniel McCann, Sean Savage, and Mairead Farrell were selected to carry out the attack planned in Operation Flavius.

Beginning of the end

Despite the IRA’s extensive security precautions, Savage and McCann were spotted in November 1997 in Spain by terrorist experts from Madrid’s Servicios de Informacion office. After observing their movements and relaying the findings to MI6 (the British foreign intelligence agency) and SAS headquarters, it was generally agreed that the duo could only be in the region for one of two reasons – to carry out an operation against the 250,000-strong British presence on the Costa del Sol, or a British Army target in Gibraltar.

This was narrowed down in the months, followed by concentrated cooperation between British and Spanish intelligence and counterterrorism experts. They soon agreed: the target would most likely be the changing of the guard outside the Governor of Gibraltar’s residence. It was, and although they did not know it at the time, all the IRA’s secret planning had been in vain.

Having arrived at this conclusion in November, a cover story was produced to postpone the scheduled event to March 8, 1988. The released report was that the schedule change was due to a planned refurbishing of the guardhouse. The event was deferred in order for authorities to have more time to plan their course of action against the terrorists.

On March 1, authorities documented the arrival of an Irish woman traveling under a false name, Mary Parkin. She was observed closely watching the changing of the guard ceremony on numerous occasions during the previous month. There was little doubt – she was providing advance reconnaissance for the IRA team to follow.

SAS: Time to act

The following day, the determination was made by the Joint Intelligence Committee in London (on which the SAS had a liaison officer) that an attack was imminent and the time to act had arrived. So, on March 3, a team of sixteen operators from the SAS Special Projects Team was dispatched to Gibraltar – all coming on different flights and at different times. Their mission, code-named Operation Flavius, was to conduct the arrests of all suspects before they could carry out the attack.

Having confirmed the target, it was up to the SAS to decipher how the IRA would carry out its mission. Intelligence provided to the SAS team indicated that the terrorists were heavily armed and that the method of attack would almost certainly via a remotely-detonated bomb planted in a car and parked next to the change of command.

Deadly force authorized

For this reason, the orders given to the SP Team involved in Operation Flavius were expanded to authorize the use of deadly force ‘if those using them had reasonable grounds or believing an act was being committed or about to be committed which would endanger life or lives and if there was no other way of preventing that other than the use of firearms.’

This was an important distinction, as terrorists planning to set off a remote-controlled bomb could do so with the flick of a switch on a miniaturized detonator. To an experienced operator, this meant that any untoward movement – a hand moving to a pocket or bag – could indicate an attempt to set off the remote and detonate the bomb.

Endgame

At 2:50 p.m. on March 6, 1988, the three IRA men were spotted entering the town center. Savage had been watched earlier as he drove a white Renault 5 car into the main square and parked it next to the site where the changing of the guards would later take place. After strolling through the square for a short time, they met again in front of the Renault. Minutes later, the three left the area and began walking back toward the border to the north.

Possible car bomb

Seizing the opportunity, a SAS bomb disposal expert ran to the Renault and quickly inspected it for any signs of a bomb. He reported back that while he could not see an explosive device, it was still possible that the vehicle could contain one – a fact that could not be determined with certainty without actually removing the car to a safe location and dismantling it. This, of course, was out of the question, and the SAS had to assume that the Renault did contain a bomb. Acting on the information, Gibraltar’s police commissioner signed over authority for the arrests to the SAS.

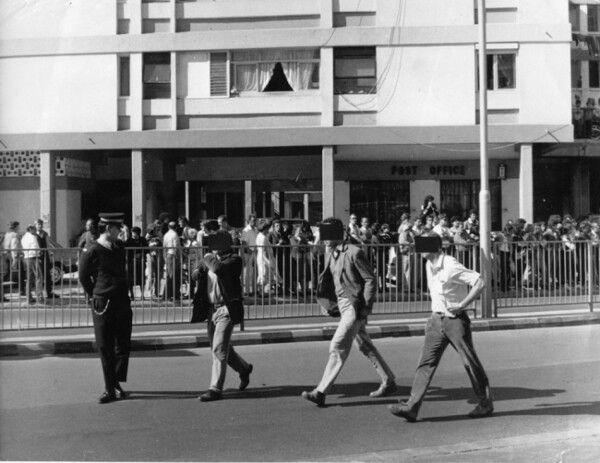

On the ground, a four-man SAS team trailing the IRA trio was given the go-ahead to arrest the suspects and prepared to move in. Back at the operations center, the police chief called over the radio for one of his men to return to base so that he would have a vehicle ready to transport the terrorists to jail. The officer acknowledged the call; however, he found himself stuck in a long line of traffic. To expedite his return to base, he switched on his siren and pulled out onto the wrong side of the road.

Aggressive movement

A short distance away, the sound of the siren rang out across the town square. Already tense from the days spent planning the upcoming car bombing, McCann and Farrell, who were walking together, froze. Looking around, they spotted the SAS operator, who was then only 10 meters away. McCann then made what was deemed an ‘aggressive movement’ across the front of his body, and the closest SAS trooper opened fire, striking him once in the back. In that instant, Farrell made a move for her handbag. Believing that the bag might contain the detonator, the trooper fired twice, killing her instantly. McCann, wounded but still believed to be a threat, was then shot five more times.

Savage heard the gunfire a short distance away and spun around – directly into the two-man SAS team assigned to arrest him. However, he was ordered to halt instead of raising his hands; he put his right hand down to his jacket pocket. Again believing that a remote device could be concealed anywhere on his body, both operators opened fire, striking Savage 16 and 18 times. Within seconds, all IRA terrorists were killed, and an attack that would undoubtedly have killed and maimed scores of civilians was prevented.

Aftermath

In the months that followed, a major inquiry into Operation Flavius and the incident was launched amidst accusations that the SAS had never intended to arrest the trio but instead had been sent as part of an assassination team formed to eliminate three of the IRA’s top operatives. Civilian eyewitnesses to the shootings claimed that the IRA operatives made gestures to surrender but were shot anyway.

Investigation

The investigation about Operation Flavius also revealed some disturbing facts: none of the three, McCann, Farrell, or Savage, were armed at the time of the shootings. Nor did any of them have in their possession a remote detonation device. Finally, an examination of the Renault found no trace of explosives. A board of inquiry conducted eventually acquitted the SAS shooters. However, Operation Flavius remains a point of contention in Great Britain to this day.

It’s all about their genuine and honest held belief and the intelligence strongly pointed towards a mass casualty incident if they hadn’t taken the action they did.

They were between a rock (no pun intended) and a hard place. They carried out their duty without fear or favour.