SASR in Afghan ambush refers to the events from late August 2008. A series of events will be always remembered by the SASR operators who fought bravely alongside their American friends.

On 26 August 2008, 1 Troop SASR (Australia’s Special Air Service Regiment), made up of four six-man patrols, flew 80km to American Forward Operating Base Anaconda (FOB Anaconda) near Khas Uruzgan intent on finding a Taliban leader they thought was in the area. No sooner were they on the ground than intelligence came in that their target had been spotted elsewhere – and the Aussies were stuck at FOB Anaconda for several days waiting for a return flight.

Two hostile valleys

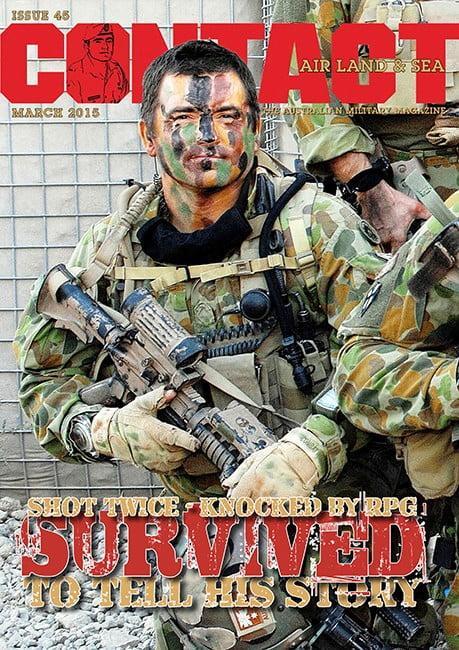

Rather than kick back and relax, however, the Aussies asked their American hosts if there was anything they could do to help. Among those Aussies was SASR team leader Sergeant Troy Simmonds. And this is how he remembers the next few days…

In truly understated Aussie fashion, Sergeant Troy Simmonds, a veteran of Somalia, East Timor and Iraq, recalls asking the soldiers from the American 7th Special Forces Group, “We’re here for a couple of days – where’s your hot spots?”

“Well, we have these two valleys we can’t get into,” came the reply.

Up for anything, the Aussies said, “We’ll have a go at them – make ourselves useful while we’re here”. So, ‘a plan was hatched’ Sergeant Simmonds says.

Sniper patrol

The plan would see a sniper patrol clandestinely sent out on foot under cover of darkness to reconnoitre and set up an ambush and wait for a vehicle patrol that would overtly go out the next day. As planned, five Humvees set out for one of the troublesome valleys, heretofore designated a no-go zone, to stir things up.

It didn’t take long.

The snipers spotted three Taliban moving into what was thought to be a command position some 500m away, and took them out. When a heavily armed ‘technical’ arrived to collect the bodies, the combined Aussie/American patrol fought through using rifles and grenade launchers, aided by the snipers.

A follow-up battlefield clearance confirmed 11 enemy down. That night, with the tactic proven, the SAS sent out two foot patrols to the second valley.

At 0400 hr on 2 September, 12 SASR operators plus two Aussie engineers and explosives detection dog Sarbi joined 10 Americans aboard the middle three of a five-Humvee convoy. The first and last vehicles contained 10 Afghan soldiers each.

Near the mouth of the valley, the Aussies hopped out of the vehicles and clambered up into the hills to set up yet more ambush positions while the vehicles waited in the green zone before moving into the narrow valley. The convoy quickly attracted attention, but their movement in turn only brought the enemy to the attention of the waiting Aussies – as planned. Another seven enemy were killed in short order.

Sergeant Simmonds’ patrol spotted another nest of Taliban, armed with rifles and RPGs about 800m away, but this group had children among them, so they were not engaged. As the day wore on, the decision to return to base was made. The 12 Aussies who rode out with the vehicles married up with the Hummers while the two sniper teams went back over the mountains and started their long walk back to base.

SASR in Afghan ambush

The valley was so narrow and rough that the vehicles had to simply turn around and go back along the same track they had used to get into the valley – tactically not an ideal choice because the hornets’ nest had been well and truly kicked. It was 3 pm and the Taliban were pissed. Enemy radio chatter rallied all available men to, “Kill them – kill them all”.

Mortars began to rain down, quickly followed by hails of bullets and rocket-propelled grenades. On foot, using the vehicles for cover, the allied patrol returned fire with everything they had – rifles, grenade launchers, 7.62mm and .50cal machineguns, and 66mm and 84mm anti-armor weapons.

But the enemy were in much better positions – high ground, good cover, and concealment, estimated at about 200 strong and “pouring a shit-tonne” of ordnance down on the convoy. The rough ground and the dismounted troops meant progress was agonizingly slow. An American soldier firing a .50 cal machine gun was hit in the arm early in the fight and, after rendering first aid, an Aussie jumped up behind the weapon to keep the big gun going.

Close air support was called and 500lb bombs silenced the mortars and slowed the bullets just a little. But the convoy was far from saved. Having moved just 1km from the start point, they were still under heavy fire from at least two directions.

American Sergeant Greg Rodriguez was next to go down – shot in the head and killed outright. Even while two Aussies carried his body to a Humvee the already-dead sergeant copped another two rounds in the back, missing his Aussie aides. About then, a Chinook helicopter was spotted flying past at some distance and everyone knew it would have Apache escorts.

Australian joint terminal attack controller Corporal Gibbo attempted to call them in, but the Dutch Apaches were reluctant, citing rules of engagement. Corporal Gibbo decided to move to higher ground to assist the pilots to pinpoint targets, but he was shot in the chest and was in a bad way.

The Apaches were eventually and unceremoniously told to “Fuck off then” if they wouldn’t help.

About now, the lead Afghan Hummer stopped, the Afghan soldiers trying to use its bullet-proof glass for cover – effectively halting the entire convoy in the kill zone. Another American went down with gunshot wounds to the legs – then another Aussie – and another. Sergeant Simmonds was on one knee, beside an American, returning fire in the direction of muzzle flashes, which was all he could see of the enemy on his side of the vehicle.

“At that stage, we were getting shot at from all directions, so there wasn’t anywhere you could really hide,” he says.

“Bullets were landing all around us – it was kind of like rain on the water in the dust.

“One of those bullets landed very near me and ricochet’d into my calf.

“I turned to the guy next to me and I said, “I just got shot”.”

“God damn, so did I,” the Yank yelled back.

Sergeant Simmonds stayed upright, however – thanks to adrenaline, training and a desperate desire to live through this. Moments later, while ordering two of his men to go forward to get the lead vehicle moving again, an RPG landed directly between Sergeant Simmonds and the two other Aussies.

The explosion blew all three off their feet and everyone who witnessed the explosion were certain their sergeant and colleagues were dead. Lying on the ground, peppered with shrapnel all up his left side and with a massive ringing in his ears, Sergeant Simmonds says he couldn’t feel his left arm, like it was numb from sleeping on it.

“I couldn’t see a thing with all the dust the RPG had kicked up and I was actually afraid to feel for my arm because I was scared it wasn’t there.

“But I eventually reached over and was relieved to find my arm was still attached – and the feeling started to come back into it.”

The other two Aussies, although also wounded by shrapnel, got back on their feet and went forward to the lead vehicle as instructed. One banished the Afghan driver to the back and jumped into the driver’s seat, taking direct control of the situation.

Sergeant Simmonds got up and attempted to move to where the American commander was, to appraise him of the situation and why his men were going forward, but was shot at from close range by two Taliban behind some rocks. He began to shoot back.

Suddenly, his own rifle, which he had in his shoulder with his cheek on the stock, carefully aiming, kicked up and smashed him in the face. It had caught a round in its ejection port, undoubtedly saving the sergeant’s life. His weapon was now useless.

Seconds later Sergeant Simmonds felt another massive pain in his lower body, which again knocked him down.

“I didn’t actually know where I’d been hit because I was already covered in blood anyway.

“What had happened, I found out later, was the bullet went through my right bum, past my bowels and my bladder and lodged in my left hip joint.

“In surgery later they had to leave it where it was – it would have been too complicated and dangerous to take it out.

“The surgeons said I was extremely lucky with that shot. They said they tried to push a rod through the entry wound to where the bullet was, without going through my bowel or vital organs – but couldn’t.

“But somehow the bullet had gone through one side of my body to the other without nicking anything vital.

“Anyway, at the time, I thought I was just winded, so I got up and went to the American captain in the Humvee.

“I was sort of dodging bullets all the while because there were bullets hitting the car all over.

“I opened the door and the captain was sitting there with a radio to both ears, talking to two different people.

“I told him that my guys were going forward to get the lead vehicle moving and assured him that everyone else was on or near a vehicle and ready to move.

“As I closed the door, a burst of machinegun fire hit the back of the car, so there was no way I could go that way.

“So I dropped on my back and actually shuffled underneath the car.

“I was surprisingly calm under there and had a little time to go over our situation in my head.”

Suddenly the Hummer started to move and Sergeant Simmonds grabbed a hold of something to go with it. But the ground was too rough to get dragged over, and he eventually had to let go – and try to avoid being crushed between the rear diff and the jagged rocks. Clear of the vehicle, which was still moving at walking pace, badly wounded in the both hips, with the rain of bullets still dancing in the dust all around him, Sergeant Simmonds “hobbled like an instant old man” after the Hummer.

As he got close, another RPG burst above the vehicle and knocked him down again and sprayed the men inside with shrapnel. Some shrapnel from this RPG also sliced through the leash tethering Sarbi to her handler, Corporal David ‘Simdog’ Simpson.

Sarbi took off – and 14 months later stamped her own pawmark on the pages of Australian military history when she was recovered during an American SF raid on a Taliban compound, returned to her super-grateful owners and eventual retirement in Australia [where she eventually died of old age in 2015].

Catching up with the Hummer, Sergeant Simmonds found there was no room for him inside the vehicle nor were any of the men in it in a fit state to help him, so he staggered around the front where he managed to lodge himself in the gap between the radiator and the bullbar.

Just then, another RPG airburst above the back of the vehicle peppered those inside with even more shrapnel.

One of those wounded this time was an Afghan interpreter, who was badly hit in the head and thrown out of the vehicle – and saved by Trooper Mark Donaldson who was later awarded Australia’s highest gallantry award, the Victoria Cross, for his actions.

Four other gallantry medals were awarded for surrounding events, including a Medal for Gallantry to the Aussie who took control of the lead vehicle.

Deliberate Target

Curled in a foetal position on the front of the Hummer, Sergeant Simmonds became a deliberate target again. Rounds started peppering the bonnet and the bullbar, inches from the badly wounded, almost deaf, covered in blood, armed with a useless weapon and allbut helpless Aussie, who was wearing only the shredded remnants of what was once a uniform.

“I thought it was just a matter of time before I got hit again,” he says.

“I remember actually thinking, “I’ve been hit in the body already and I think I’m alright, but if I get hit in the head then it’s all over”.

“I didn’t have a helmet on so I was quite worried about my head.

“Then I spotted the heavy tow chain wrapped around the bullbar, so I unravelled that and wrapped it around my head – while bullets were still pinging on metal all around me.”

But now a new danger seeped into his mind. The patrol had a strong suspicion that the enemy may try to cut them off by planting an IED in the pass up ahead, which would really finish them off.

“It was a very narrow pass – not much more than a vehicle width, with rock on either side.

“Anyway, my guy who was now driving the front vehicle did a bit of a dynamic move and went through the pass sort of up on an angle, with one set of wheels up on the rocks, and he got through.

“So all the other vehicles did the same thing, following in his tracks, and we all got through – under a huge amount of fire.

“They had machineguns on us from every angle, but we got through and gradually the fire started to ease off – and that’s when I got really nervous.

“I was thinking, “OK we got away with that – now we’ll probably hit an IED or something”.

“And riding behind the bullbar is probably not the best place to be when a vehicle hits an IED.”

Reflecting on the ambush years later, Sergeant Simmonds says it was probably a bit selfish worrying about himself instead of his men, but concedes it was probably human nature too – and there wasn’t a lot he could have done for anyone in his precarious, exposed position anyway.

But, as luck would have it, there was no IED on the route back to base and the convoy rumbled into FOB Anaconda to the waiting arms of a plethora of colleagues eager to triage the wounded and get the worst of them evacuated as quickly as possible.

“The triage all went very well. They grabbed us and put us on stretchers and took care of us really well.

“They flew me and a couple of others to Tarin Kot, where there had just been a turnover of surgical teams and so the surgeons who worked on us were a collection of top people from Melbourne and Sydney – all reservists.

“The bullet in my lower leg wasn’t a big issue. It was a ricochet so it had broken up before going in. So they took out all the pieces easy enough.

“Those wounds took a while to heal up though.

“Like I said, the bullet in my hip had to be left in place – and I was also shitting blood for about 12 months from all the trauma around that area – but otherwise my recovery was fairly OK.”

Recovery and rehabilitation

Sergeant Simmonds made a good recovery and was posted to the training squadron at Campbell Barracks, Swanbourne, home of the SAS, to help on the SASR selection course and train new guys in the basic skills of the SAS soldier. He says he really enjoyed that role for a couple of years. He also enjoyed plenty of time recuperating and spent lots of time with his wife, who had only seen him for three or four months a year since he joined the SAS.

Inevitably, however, he was posted back to an operational squadron and again deployed to Afghanistan.

“I had some trepidation going back there, but this time I wasn’t going outside the wire.

“My job on this trip was helping to plan missions and assist and advise young officers in how the SAS does business.”

Now retired from the SAS, Troy Simmonds says he feels no ill effects from his service generally nor from the ambush that almost took his life.

“I saw some pretty bad stuff over there, but I think I have the capacity to put things in perspective and to compartmentalise them.

“It’s almost like I can look back on that part of my life and see that I was like acting a role at that time, and now I’m in a different role.

“I know some blokes do suffer from psychological issues after something like that, but I don’t – or I don’t think I do.

“I can think about it and talk about it and look at photos or videos from over there and it doesn’t have a massive emotional affect on me.”

Troy Simmonds spent 22 years in the Australian Army and did six tours of Afghanistan with the Special Operations Task Group.

The Battle of Ana Kalay lasted about two hours and resulted in one US KIA, with one wounded. Of nine Aussies wounded, one was considered life-threatening at the time, but all survived.

After-action assessments put the enemy death toll at about 80.

* This story was published in CONTACT Air Land & Sea issue 45 on 1 March 2015.