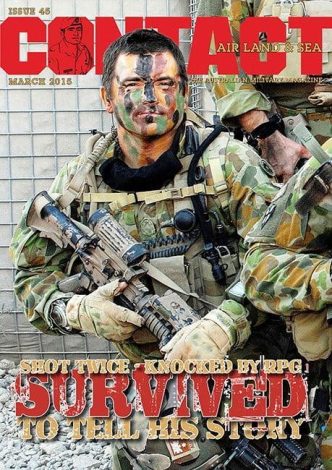

Operation Chavin de Huantar was a military and hostage rescue operation in Lima, Peru, performed by elite Peruvian special forces on April 22, 1997. The raid involved a team of one hundred and forty-two commandos of the Peruvian Armed Forces. They stormed the Japanese ambassador’s residence and freed the hostages by the terrorist organization Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA).

Operation Chavin de Huantar is considered one of the most successful hostage rescue operations in modern history.

Introduction

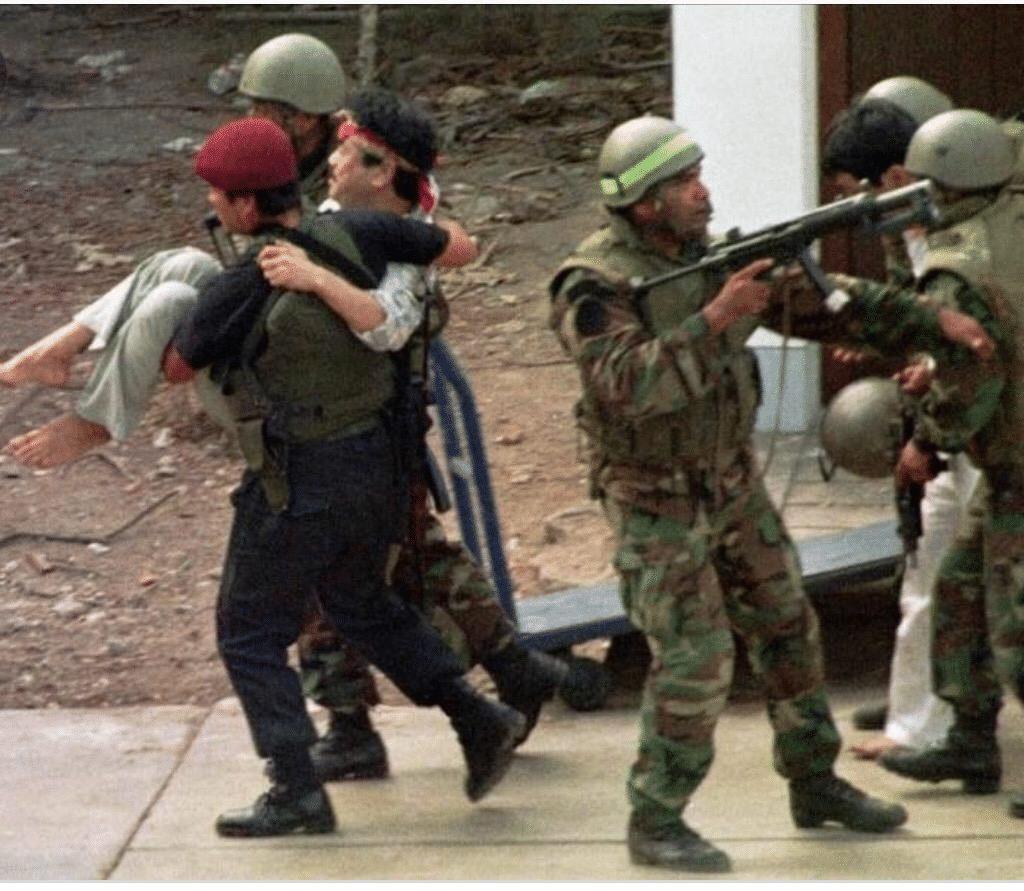

On April 22, 1997, a composite force of Peruvian elite forces surprised the world by performing an operation that everyone thought Peru was incapable of. These troops stormed the Japanese ambassador’s residence (see figure 1). For more than four months, 14 Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (Movimiento Revolucionario Tupac Amaru—MRTA) had been holding 72 hostages.

The MRTA had conducted a daring assault on the ambassador’s residence on December 17, 1996, during a celebration of the Japanese Emperor’s birthday. Initially, the MRTA had taken more than 500 hostages but had released all but 72 during the period leading up to the assault by Peruvian forces.

MRTA made a series of demands:

- The release of their members from prisons around Peru (including recently convicted US activist Lori Berenson and Cerpa’s wife).

- A revision of the Government’s neoliberal free-market reforms.

- They called for the end of Japan’s foreign assistance program in Peru, arguing that it benefited only a narrow segment of society.

- They protested against the cruel conditions in Peru’s jails.

Operation Chavin de Huantar lasted only 22 minutes. The Peruvian special forces sustained only 12 casualties: one hostage, two soldiers dead, and nine wounded. All 14 MRTA members lost their lives. Internationally, the operation was hailed as daring but inevitable. Terrorism had to be crushed, and President Alberto Fujimori’s wager in risking so many high-profile lives paid off.

Peru’s determination to end the crisis without giving in to the terrorists’ demands elevated its reputation worldwide to unprecedented levels. In the end, however, the success was due more to the terrorists’ own mistakes and boredom than to any distinctive capabilities of the Peruvian counter-terrorist forces.

The day after the rescue, President Fujimori explained that the operation was named after a pre-Incan civilization called the Chavin, which flourished in what was then (pre-1400s) considered Huantar. Huantar was located in what is now the Ancash Department of Peru. The Chavin hid from their enemies in tunnels underneath their temples when attacked. Thus, when the concept of this assault was formulated in late December 1996, President Fujimori thought that the example of this group would be an appropriate name for the operation.

Peruvian Counter-terrorist Capabilities

Although Peruvian armed forces fought insurgents and terrorists for over a decade, the Peruvian special forces (SF) required three months to prepare for the assault. Four days after the MRTA successfully entered the ambassador’s residence, the armed forces began developing plans to rescue the hostages should peaceful negotiations fail.

Joint task force

A 140-man joint task force—comprising 70 National Police members and 70 personnel from army, navy, and air force special operations units—was charged with the planning and eventual conduct of the operation. While the task force prepared for the actual rescue, the National Intelligence Service (Servicio Nacional de Inteligencia—SIN) set up an intelligence headquarters next door to the ambassador’s residence, in the same house the terrorists had used to launch their attack. Additionally, the SIN was tasked with coordinating all operations against the MRTA.

The Peruvian Government refused the terrorists’ demands and adopted a standoff strategy from the outset. While the Government led the terrorists into protracted negotiations and the task force prepared and trained, police officers guarding the residence conducted a series of harassing activities.

Psychological activities

The residence’s water and electricity were cut off; in addition, heavily armed police officers marched in front of the residence, threw stones into the compound, played loud music, occasionally fired shots into the air, and may have had a television reporter enter the residence, ostensibly for an interview but primarily to collect intelligence on the positions of hostages and weapons.

The harassing activities and the protracted negotiations relaxed the terrorists and caused them to grow confident that world opinion would prevent Peru from launching an armed attack. Consequently, the 14 MRTA members entered into a daily routine. As early as January 9, a Lima radio station announced that a task force directed to conduct contingency operations against the ambassador’s residence was undergoing intensive training.

Underground tunnels

In early March, the issue of tunnels being dug into the compound was also reported in the press, but this did not seem to affect the terrorists. Even the daily rumblings of trucks carrying heavy loads (which should have confirmed the tunneling operation) did not seem to disturb the terrorists; their response was to move the hostages to the second floor of the building. This move eventually reduced the danger of injury to the hostages from the initial blast through the residence floor.

The Final Assault

The night before the final assault, half of the task force assembled close to the residence and slowly began to take their positions. Seventy policemen stationed themselves around the perimeter of the house. Eight sharpshooters took positions on the surrounding rooftops. The remaining personnel of the assault force had been divided into three groups.

Order for assault

In 1517 (Lima time), President Fujimori issued the order for the task force to assault the Japanese ambassador’s residence. Six minutes later, the residence’s main living room and kitchen floors exploded, killing several terrorists playing soccer in the living room. The explosions were caused by charges that had been carefully placed in a series of tunnels dug under the house and grounds. At the same time, the three assault groups converged on the home, conducting what can only be described as a rapid, violent assault against the MRTA members.

Attack from the underground

One group emerged from the underground tunnel into the side of the residence, attacked the service areas, and climbed to the second floor. A second group, which had breached the compound’s western gate, assaulted the residence’s main door and the north and south sides of the building. The third group scaled the northern outer perimeter wall. Breaching charges were used to open up the residence and rescue the hostages. At 1524, 1 minute after the first explosion, commandos entered the residence itself. Rescue of all 72 hostages took only 28 minutes, and by 1600 even the MRTA flag, which had flown in defiance on the roof of the residence, had been burned.

Weaponry and gear

The assault force employed a variety of light automatic weapons—AK-47s, AKMs, P-90s, UZIs, mini-UZIs, and Heckler and Koch MP5s—as well as various handguns. Sniper teams were equipped with FN FAL rifles with optical scopes. All assault task force members wore the army’s SF uniform: olive utility uniform, olive armored vest, and combat boots. The 70 members of the National Police, which secured the perimeter of the facility, were dressed in berets, black or olive armored vests, dark T-shirts, utility trousers, and combat boots. Armed primarily with AK-47s and AKMs, the force also included several armored vehicles with machine guns used in the cordon.

Valuable Lessons

Operation Chavin de Huantar provides valuable lessons in conducting this type of operation. First is the necessity for detailed planning. The Peruvians began planning this operation within several days of taking the hostages. Media reports following the rescue have provided details showing the depth and thoroughness of the planning for this mission. Secondly, while hints of a planned rescue circulated in the media, details of the plan itself, as well as the preparation and rehearsals, were closely held.

This was just good operational security! Thirdly, Operation Chavin de Huantar achieved a level of tactical and strategic surprise that can only be termed classic: The entire world, not just the MRTA terrorists, was caught off guard.

Peruvian SOF was considered incapable at the time

There are several other essential points to be made. Peruvian special units, both military and police, had generally been considered incapable of conducting a rescue operation. Peruvian leaders surprised everyone by selecting their best people from different military and police units and forming a single force for this mission. Another critical point is the skillful negotiation process the Government of Peru used to its advantage. By drawing out the time of the negotiations, the Government provided the rescue force with time to train and prepare for the operation.

Useful intelligence work

This long timeframe is also credited with causing the MRTA to lose its focus and intensity, which ultimately degraded its security posture. Another key aspect is the efforts of the Peruvians to gather information and process it into useful intelligence. Information gleaned from media reporting following the rescue has indicated the detailed information gathered about the facility and the MRTA personnel, from shortly after the initial taking of hostages until just before the actual assault.

Conclusions

Although Peru’s counter-terrorist capabilities may be rated as high, it is important to remember that several factors worked in the task force’s favor. The strategy used in dealing with the terrorists may have been the most important factor. Protracted negotiations and the skillful use of the media reporting the world’s rejection of an armed assault on the residence certainly contributed to the terrorists’ relaxed mode and their ultimate downfall. Furthermore, it took more than four months to resolve the crisis, primarily because the task force needed planning and intense training.

Additionally, the task force may have considered the underground tunnel an absolute necessity for a successful operation. Weeks after the assault, there were reports that miners experienced digging through sandy soil had been brought from southern Peru to build the tunnel. The Special Forces carried light armament into the residence, and a five-to-one ratio in manpower gave the Special Forces an overwhelming advantage. The surprise effect of the explosion coming from inside the residence contributed to stunning the terrorists and may have saved the lives of many hostages.

While the operation had a certain degree of risk (both tactical and political), it was planned and conducted in a very professional manner that contributed to the mission’s success.